How Your Attachment to Possessions Hurts Your Finances

Explaining The Endowment Effect

“It is preoccupation with possessions, more than anything else, that prevents us from living freely and nobly.”

-Bertrand Russell

Welcome to another installment in my ongoing series called “Money On My Mind,” where I publish articles to help you deal with the psychological aspects of managing money. Check out past editions of the series here.

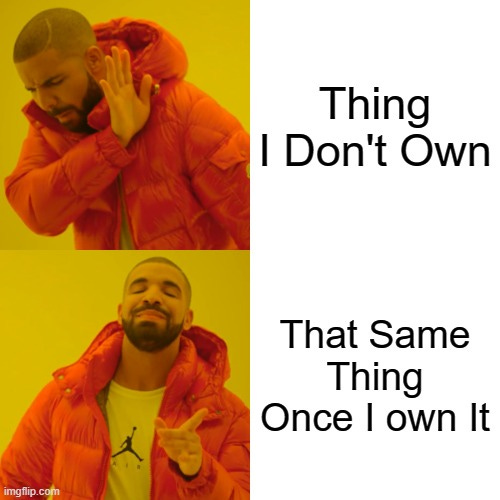

We continue our exploration of cognitive biases by unpacking the endowment effect.

Continue reading to learn:

Why we have emotional attachments to the things, we own.

How those attachments can hurt our finances.

How culture and gender impact the endowment effect

The impact the endowment effect can have on your career

Three tips to avoid the endowment effect

What is the Endowment effect?

Richard Thaler defined the endowment effect as the “underweighting of opportunity costs.”

One of the most important lessons in economics is that every decision has an opportunity cost; what we don’t get by choosing one action over another.

Let’s say you are thinking of selling your house. Similar homes in your neighborhood are selling for an average of $500,000. But you decide to list your house for $600,000.

You tell yourself it’s because of the new renovations or that you have a slightly bigger backyard than your neighbors. In reality, you overvalue your home because the thought of losing your house is more painful than not having someone pay you for the true value of your home. The opportunity cost is the money you never receive because you listed your house too high and didn’t sell.

Everyone wants to feel like a savvy deal maker

A widely accepted explanation for the endowment effect is loss aversion; we are afraid to lose the things we have, so we overvalue them. But a 2012 paper by Ray Weaver and Shane Frederick throws some cold water on that theory. Weaver and Fredrick argue that we place such a high value on our possessions because we are afraid of making a bad deal. To quote the paper:

“The endowment effect is often better understood as the reluctance to trade on unfavorable terms.”

Every transaction has two sides; a buyer and a seller. Both sides of the transaction want to feel like they won the deal. Consider a transaction where someone is selling a book to another person. The buyer doesn’t want to buy the book for a price higher than their value of the book, and the seller doesn’t want to sell the book for a price lower than their value of it.

Imagine I want to sell you a book on how cognitive biases impact your financial decision-making. The book sells for $19.99, but you are only willing to pay $14.99 for the book. But I don’t want to sell you the book for $14.99 because I don’t want to feel like I am diminishing the value of my work (and because authors have razor-thin margins— but that’s beside the point.)

The $5 gap between what you’re willing to pay and what I am willing to sell the book for is the difference between the market price and your personal valuation of the book. According to Weaver and Frederick, this is what causes the endowment effect.

In other words, it’s not that we are afraid of losing our possessions that causes us to overvalue the things we own; it’s that we don’t want to feel like we made a bad deal. Weaver and Frederick found that the endowment effect goes away when the market price equals the buyer's valuation of an item. If I set the market price of my book at $17.99 and you valued it at $17.99, then you would buy it, and we would both feel like we made a good deal.